The

whole world depends on the ocean for food. Yet, fish stocks

continue to decline, while the current world population is

around eight billion: 8,024,467,500. Population in the world is, as of 2022, growing at a rate of around 0.84% per year (down from 1.05% in 2020, 1.08% in 2019, 1.10% in 2018, and 1.12% in 2017). The current population increase is estimated at 67 million people per year.

Annual growth rate reached its peak in the late 1960s, when it was at around 2%. The rate of increase has nearly halved since then, and will continue to decline in the coming years.

World population will therefore continue to grow in the 21st century, but at a much slower rate compared to the recent past. World population has doubled (100% increase) in 40 years from 1959 (3 billion) to 1999 (6 billion). It is now estimated that it will take another nearly 40 years to increase by another 50% to become 9 billion by 2037.

The latest world population projections indicate that world population will reach 10 billion persons in the year 2057.

Blue Growth as an agenda has been on the cards for a number of years without much in the way of visible movement. Why is that?

In fact things are beginning to move with the United Nations

SDG 14

(oceans & marine life below water) now beginning to bite in the quest for a sustainable balance. Though

fish stocks are still reducing in

2023, and oceans are still choked with plastics

and acidic

sea levels are

rising, with the toxicity of seafood being a major issue, as a health risk to

humans.

Which they keep eating, regardless of the micro plastics and

glass they are ingesting through ignorance. Then there are

the carcinogens,

causing cancers

and sterility issues.

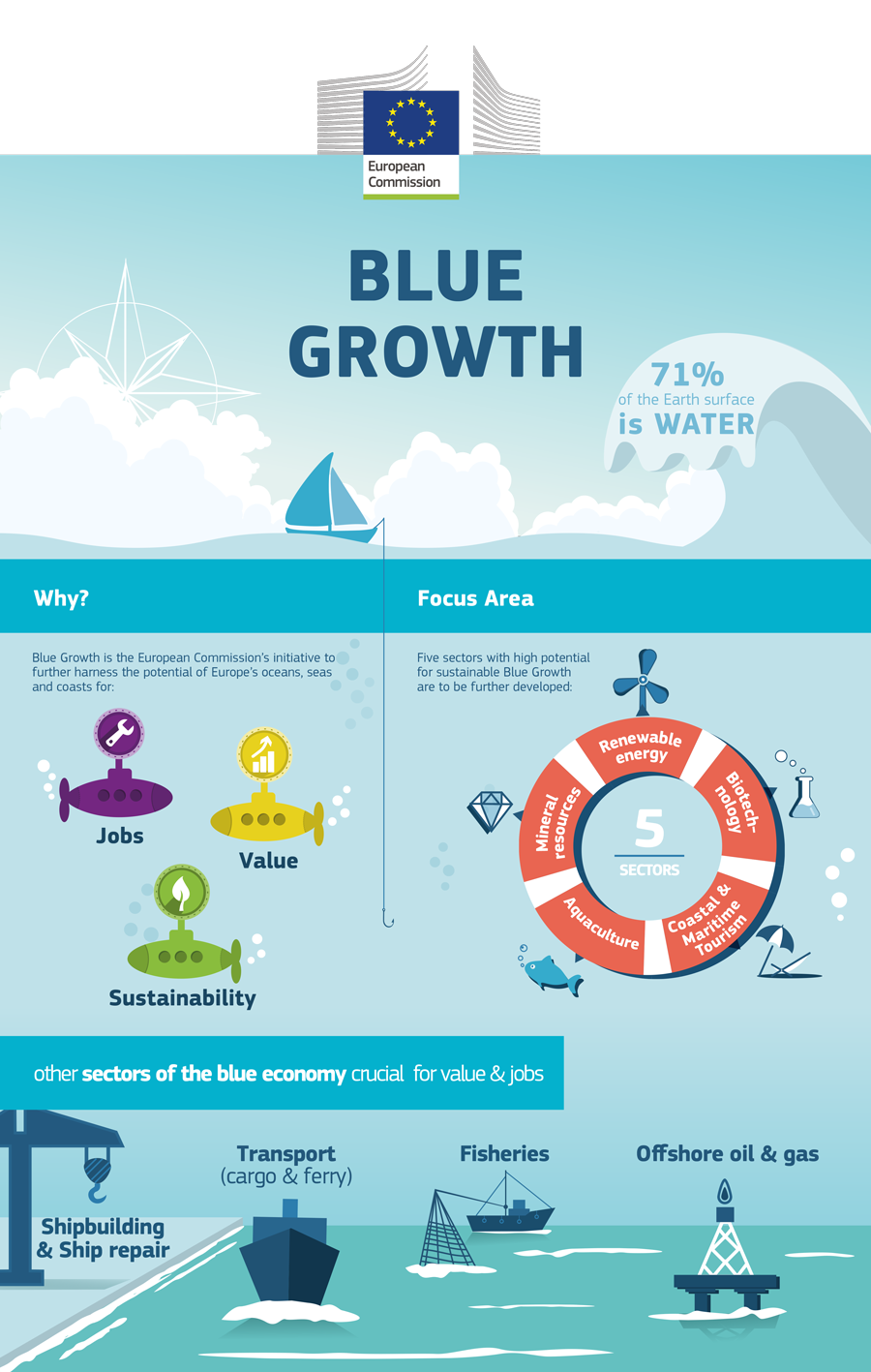

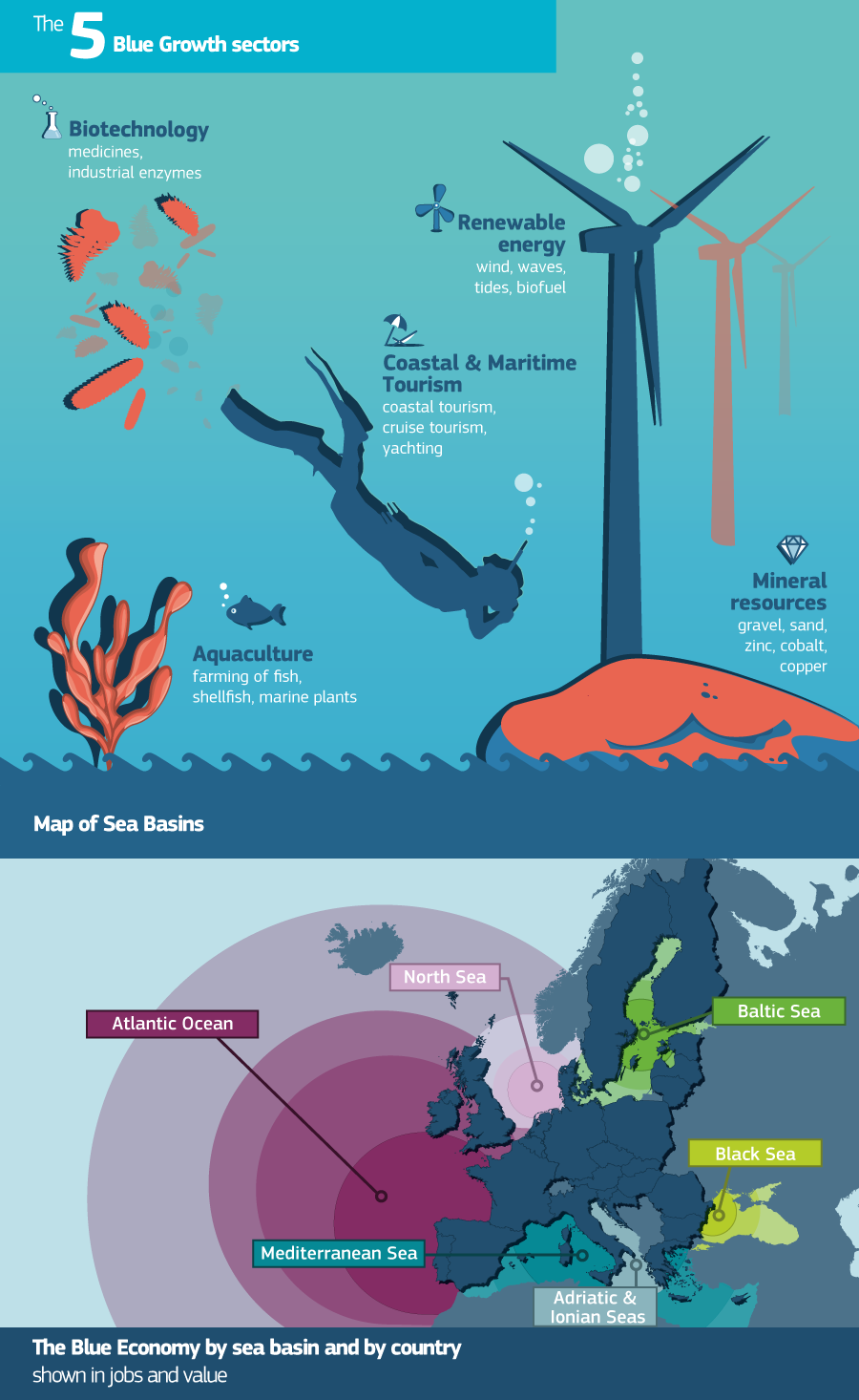

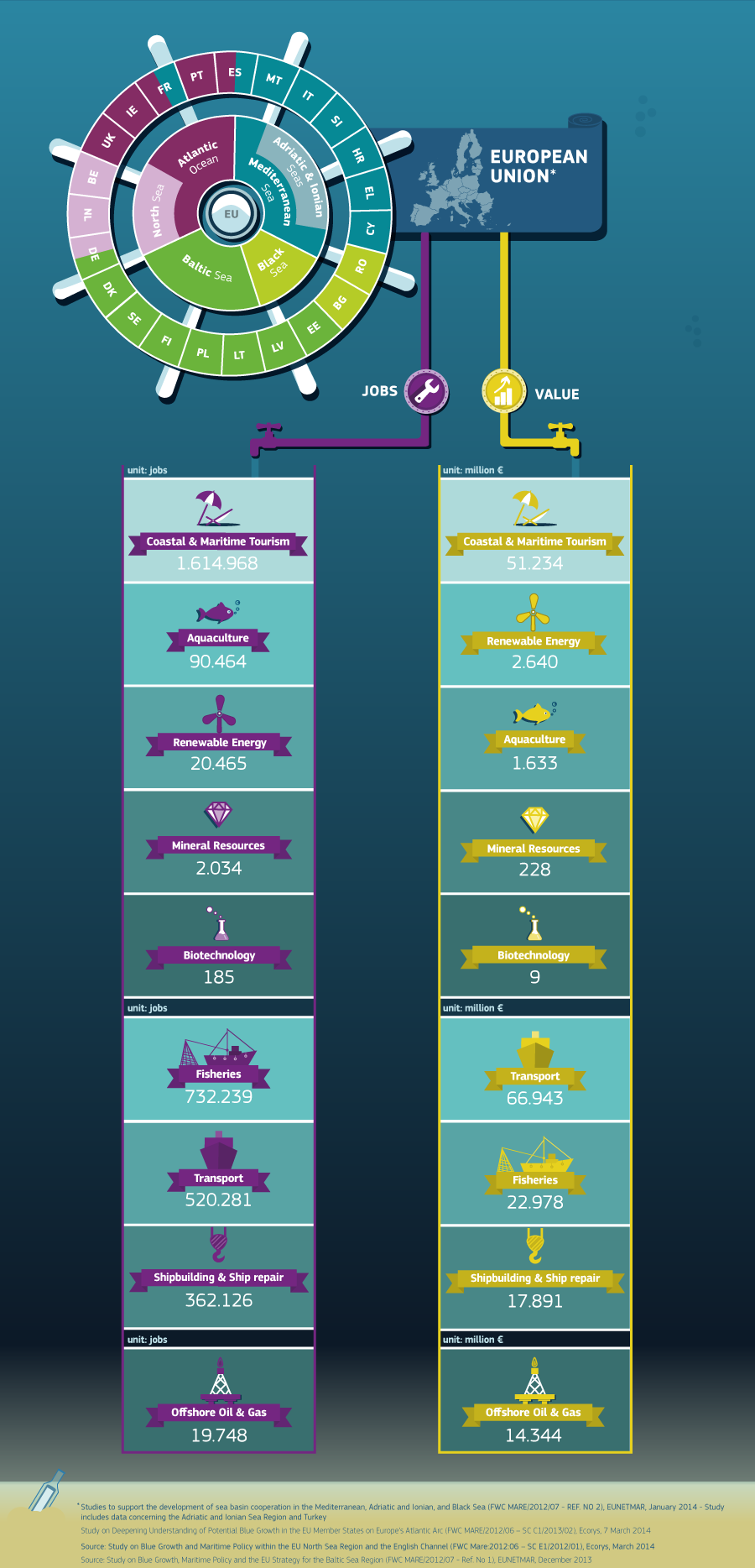

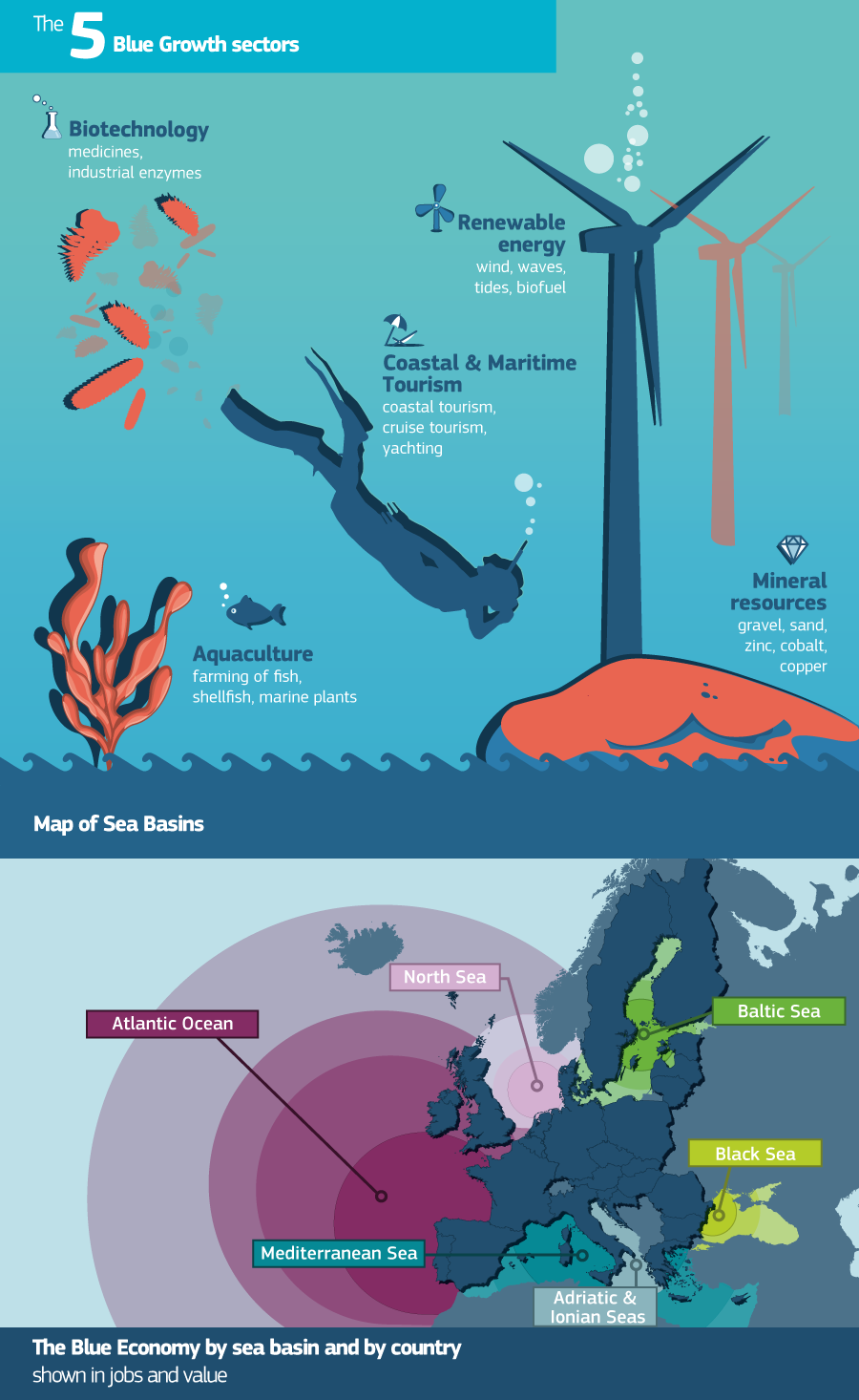

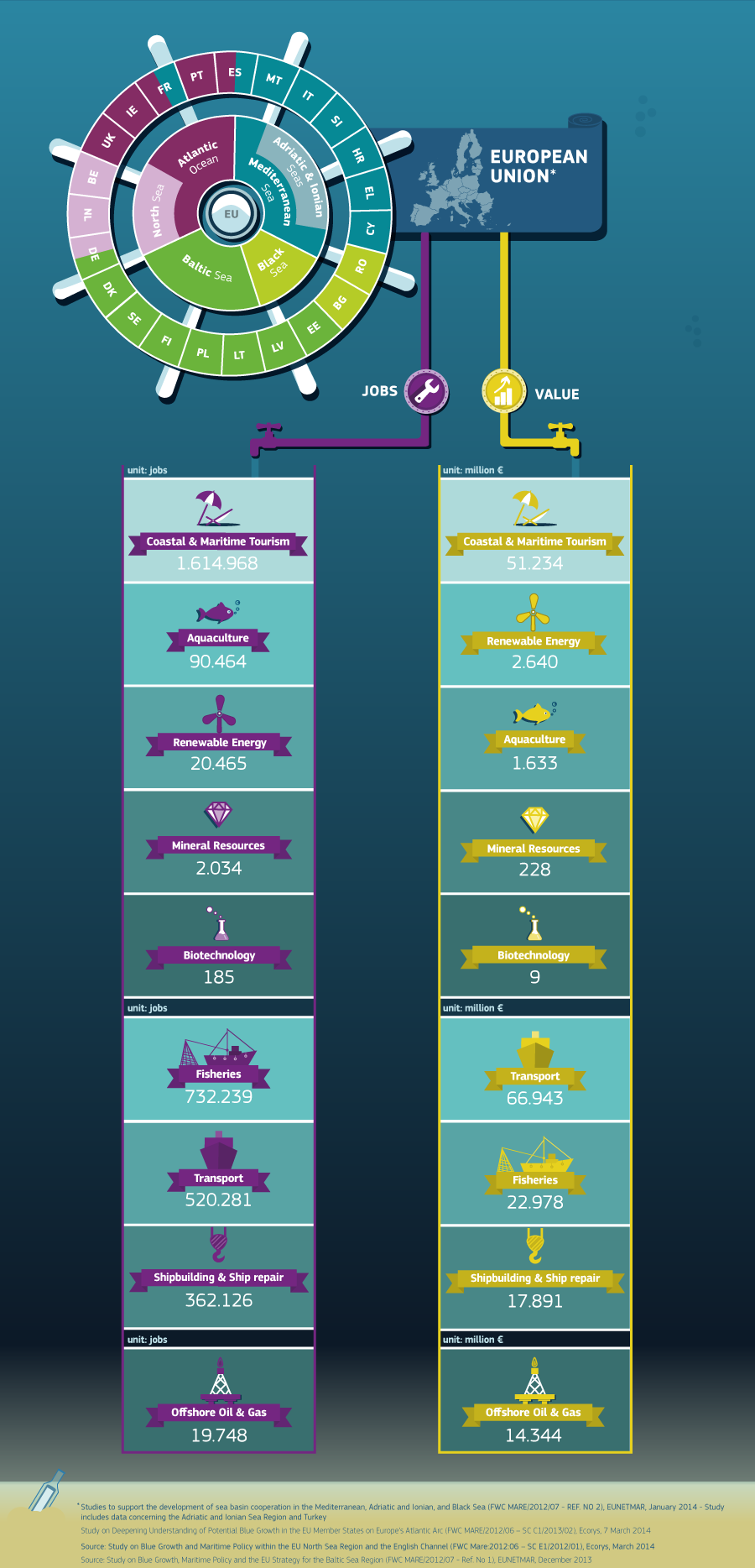

WHAT IS BLUE GROWTH ?

Blue Growth is the long term strategy to support sustainable growth in the marine and maritime sectors as a whole. The 'blue' economy represents roughly 5.4 million jobs and generates a gross added value of almost €500 billion a year in the European area alone. The ideal was adopted in part with reference to economics reflections by

Gunter Pauli and the Blue Economy.

In 2014, the ocean economy in the U.S., which included six economic sectors that depend on the ocean and Great Lakes, contributed more than $352 billion to their GDP and supported 3.1 million jobs.

Such figures will be equally significant for Africa, Alaska, Australia,

Canada,

China, India, Japan, South America and all around the globe. Further growth is possible internationally in a number of identified area with the appropriate incentives.

Thanks to the efforts of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Global Ocean Commission and others, the term "blue growth" is now accepted internationally with the objectives and criteria being acted on by almost all stakeholder nations who may benefit from embracing points 5-10 below.

The land based market economy, as it presently stands, is not capable of delivering to poor people as persistent rates of poverty and malnutrition demonstrate. The saying that “the rich get richer and poor people get poorer” is confirmed by the existence of poverty and unemployment. Poverty is spreading in absolute numbers mainly to our youth and more mature citizens. Governments accept this hardship and hide behind the need to pursue austerity while pursuing the impossible task to balance the budget. Proof of this is that the retirement age has been raised, an attempt to bridge the skills gap and milk those at both ends of the age spectrum - who are required to work even where there is no work.

BLUE GROWTH STRATEGY

Blue growth strategy is the latest thinking to grow our ocean economy for a sustainable future world where there is food and energy security for every country and jobs for those who want to work on or in the sea. Hence, "blue" refers to water and "growth" refers to economics.

Generally, "Blue Growth" is not location specific and there is no international strategy where each player must do certain things as part of their piece in a jigsaw. There is no world plan, agreement or fund to work to this end. Instead, each region has its own local agenda and areas of effort and concentrates on making their patch better with pockets of funding available for specific projects - as relate to targeted geographical areas.

The good news is that the concept is spreading with the work of many organizations like the United Nations

FAO

engaging positively. The UN's FAO in particular and the World Bank support location specific

projects, unfortunately, over funding using paper currency

that is unsupportable in sustainability terms, is counter

productive. What is needed as a brake to over lending and

borrowing is an Agricultural Dollar, to replace the Gold

Standard, where many nations are now in serious trouble

with massive (irrecoverable) National Debts.

Ultimately, blue growth is about gains the world over. An example of this is where improvements in ocean chemistry will benefit all nations due to the currents that continuously stir up and distribute polluted acid

water around the globe - so that non-polluting regions who are keeping their patch clean are now dirty for no fault of their own - and there is no compensation mechanism for the clean nations to make a claim on the dirty administrations - where pollution from the untidy culprits reaches the shores of another.

Rather than escalate the problem, the onus is on sharing knowledge and leading by example, such that other nations not yet at the stage where Blue Growth is high on their agendas, to help them to see the gains that raising the bar will bring for them in the long term.

MAIN BLOCKERS

We are facing four major problems that seriously hinder blue growth:

1. Ocean Pollution - poisons wild fish, also the source of feed for

aquaculture

2. Over Fishing - depletes wild fish stocks, threatening

food security & productive

fisheries

3. Climate Change - ocean acidification & fish migration

4. Over

Population - demands more fish than the oceans can at present provide

MAIN GROWTH AREAS

5. Ocean Regeneration - cleaning our oceans to preserve the resource and cleanse the toxic food chain

6. Aquaculture - now generates around 50% of world produce, mostly subject to wild

fish feed

7. Ocean Energy - offshore

wind and wave energy for clean

power

8. Biotechnology - Identifying, harvesting and producing

medicines

9. Coastal Tourism - To engage the public in ocean matters and reduce

air travel

10. Green Ships -

Cargo and cruise ships that are

cleaner, preferably zero carbon

11. Green Ports - Ports and docks that are more efficient at handling passengers and cargo

Which one of these is the most important for you depends on your point of view, but all potential solutions that stand a chance of returning us to a sustainable society, depend on every one of us recognizing the problems and doing something about it, if that is within your grasp - and that is an

Ocean Literacy issue - the problem being that most people on

planet earth are not aware that this is a serious problem. Hence, the lack of awareness is a big stumbling block, triggering the creative Ocean Awareness Campaigns of the Cleaner Ocean

Foundation: Kulo

Luna, Cleopatra's Mummy and

Treasure

Island.

DEEP

DISCOVERER - The remotely operated vehicle, Deep Discoverer, being recovered after completing 19 dives during the Windows to the Deep 2019 expedition.

Image: Art Howard, Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration.

ROVs range in size from that of a small computer to

being as large as a small truck. Larger ROVs are very heavy and need other equipment such as a winch to put them over the side of a ship and into the water.

While using ROVs eliminates the “human presence” in the water, in most cases, ROV operations are simpler and safer to conduct than any type of occupied-submersible or diving operation because operators can stay

dry and warm, or safely on ship decks. ROVs allow underwater

investigation in areas that are too deep for humans to safely dive

themselves. And ROVs can stay underwater much longer than a human diver,

without decompression, making more time for exploration.

PLAIN SPEAKING

Scientists, policy makers, business people, and the larger society need to become more precise and transparent in their language and meanings in order to effectively work together, and hopefully one day succeed in

what should be a joint goal to secure blue growth. But where

many keep on abusing the seas that feed them, egging on

other nations with a conscience to restrict their

activities. As in: "I'm alright Jack."

Governance of marine resource use is increasingly facilitated around a recently introduced term and concept – “blue growth.” This concept is essentially the newest of many recent calls for more holistic management of complex marine social-ecological systems [3], [11], [13]. However, despite use by multiple and diverse stakeholders, the term has no generally agreed upon definition. Instead, it embodies vastly different meanings and approaches, depending on the social contexts in which it is used. The potential for miscommunication is great, as scientists from different fields, as well as other stakeholders, may be using the same term but unknowingly perceiving the concept differently, leading to potential misunderstandings and possibly misguided governance outcomes. Discussion of the meanings and implications of this increasingly globally important term is badly needed. Although our contributions do not strictly define the term, we hope that those reading this Special Issue will gain a better understanding of the various definitions, as well as a heightened awareness of the constraints of, and possibilities within, the concept. More awareness hopefully will lead to enhanced communication among colleagues and across disciplines and to the convergence towards an operational definition of blue growth necessary to create comprehensive science-based policy that delivers net social and economic benefits as well as benefits the aquatic environment, in particular marine systems.

Brief historical development of the Blue growth concept

The roots of the blue growth concept can be traced back to the conceptualization of sustainable development (SD). Sustainable development - or the challenge of a sustainable use of natural resources, while at the same time securing economic and social objectives - has been a focus of the international community since the 1960s. Three large international conferences mark the main milestones in the development of the SD concept: the environmental/resource dimension was defined in Stockholm in 1972 at the first

United Nations (UN) conference on SD; the economic dimension, in Rio 1992 at the second UN conference on SD; and the social dimension in Johannesburg 2002 at the third UN conference on SD [10]. Leading up to the fourth conference on SD, Rio + 20 held in Rio in 2012, a new concept took center stage at the backdrop of the international financial crisis. The concept was “green growth”. According to the OECD “green growth means fostering economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies.3” Realizing the traction of this new concept, and the close association of it to growth derived from terrestrial ecosystems, a group of small island nation states (SIDS) emphasized the importance of the blue economy - that is the multi-faceted economic and social importance of the ocean and inland waters - and the importance of “blue

growth”. At the Rio + 20 conference, the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) supported these views and sent a very strong message to the international community that a healthy ocean ecosystem ensured by sustainable farming and fishing operations was a prerequisite for a blue growth.

Since the Rio + 20 conference, the blue growth concept has been widely used and has become important in aquatic development in many nation states, regionally as well as internationally. The FAO, for example, launched its Blue Growth initiative, the aim of which is to “secure or restore the potential of the oceans, lagoons and inland waters by introducing responsible and sustainable approaches to reconcile economic growth and food security with the conservation of aquatic resources” [1],5 and the EU´s blue-growth strategy emphasizes the importance of marine areas for innovation and growth in five sectors in addition to increased emphasis on marine spatial planning and coastal protection [4], [8].

Emerging research

Boonstra et al. [2] discuss the relevance and usefulness of the term blue growth for the development of capture fisheries, a sector where growth is often accompanied by substantial harm to marine ecosystems. The authors compare intensive and extensive growth to argue that certain development trajectories of capture fisheries might qualify as blue growth. They also highlight aspects of some fisheries that blue growth advocates might want to emphasize if they choose to consider capture fisheries, including: a) adding value through certification; b) technology development to more effcientily utilize resources in fishing operations and to upgrade their fish as commodities; and c) specialization. They also posit that the term blue growth is meant to realize economic growth based on the exploitation of marine resources, while at the same time preventing their degradation, overuse, and pollution.

Integrated management of multiple relevant economic sectors is also a central tenet of blue growth, as is a socially optimal use of ocean-based natural resources; but we do not have more than a poor understanding of possible mechanisms for the implementation of integrated policies that would actually achieve this. Klinger et al. [7] take steps to fill this gap by reviewing current challenges and opportunities within multi-sector management. They describe the roles played by several key existing sectors (fisheries, transportation, and offshore hydrocarbon) and emerging sectors (aquaculture, tourism, and seabed mining) and discuss the likely synergistic and antagonistic interactions between sectors. To help operationalize blue growth, they review current and emerging methods to characterize and quantify inter-sector interactions, as well as decision-support tools to help managers balance and optimize around interactions.

Burgess et al. [3] discuss how the complexity of ocean systems, exacerbated by limitations on data and capacity, demands an approach to management that is pragmatic. By this they mean goal- and solution-oriented, realistic, and practical. Burgess proposes five helpful rules of thumb upon which to build such an approach: 1) Define objectives, quantify tradeoffs, and strive for efficiency; 2) Take advantage of the data that you have, which can do more than you may think; 3) Engage stakeholders, but do it right; 4) Measure your impact and learn as you go and 5) Design institutions, not behaviors. These rules, if used properly, will go a long way towards encouraging development that is realistic rather than unattainable.

Hilborn and Costello [5] summarize the past and present status, as well as potential catch, abundance and profit for 4713 fish stocks constituting 78% of global fisheries. In particular they focus on three possible scenarios for how the future might look: 1. Business as usual (BAU), in which unmanaged fisheries move towards a

bio-economic equilibrium, while well-managed fisheries maintain their current management. 2. Maximum sustainable yield (MSY), in which fisheries are managed to maximize yields. 3. Fisheries reform (REF), where competition to fish is eliminated and fisheries are managed to maximize the profits. They found that for most of the fisheries, better management can result in higher profits. In order to increase yields, in some cases it is necessary to rebuild overexploited stocks; in others, we must reduce fishing mortality on stocks that are still abundant but fished at high rates; and, in some cases, fishing some stocks harder will increase the yield. They also find that Asia provides the greatest opportunity for increasing fish abundance, particularly in cases where increased profits caused by fisheries reform will ultimately lead to a reduced fishing pressure. As the oceans provide food, employment and income for billions of people, reduced fishing pressure and sustainable fisheries are critical for global food security.

Niiranen et al. [11] discuss how the lack of recognizing cross-scale dynamics can cause uncertainties to the current fisheries projections. They show how cross-scale interactions could play out in two Arctic marine systems, the Barents Sea and the Central Arctic Ocean (CAO), by discussing how they are affected by a number of processes beyond environmental change. These changes span a wide range of dimensions, as well as spatial and temporal scales. They conclude that addressing such complexity calls for an increase in holistic scientific understanding, together with adaptive management practices. This is particularly important in the CAO, where there are no robust regional management structures to rely on to curtail potentially sub-optimal developments. Recognizing how cross-scale dynamics can cause uncertainties to fisheries projections, as well as implementing well-functioning adaptive management structures, may play a key role in whether or not we are able to realize the great potential for blue growth in our world's fisheries [9], PNAS), particularly those in the Arctic.

Social innovation is the process of developing effective concepts, strategies, solutions, or other ideas that can help solve challenging societal and/or environmental problems via collaborative action by a group of actors. Social innovation can result in changing behavior across institutions, markets or the public sector, and can enhance creativity and responsible action towards a synthesis of social, economic and environmental goals. Is it possible for blue growth to enable social innovation as a strategy for the use and management of marine resources? Soma et al. (this issue) examine this issue using case studies and conclude that this may be possible, but success will be dependent on creating cooperation, inclusiveness and trust between the different actors.

Pauly [12] presents a short history of marine fisheries, highlighting the dramatic expansion of industrial fleets in the 1900s and the intrinsic unsustainability of those fisheries. Pauly then argues that while the vast majority of large, commercial fisheries lack the features that would make them sustainable or even capable of sustainability, small-scale fisheries

(including artisanal, subsistence and recreational fisheries) often possess most of these features. Small-scale fisheries could become an

important blue growth sector, assuming total fishing effort is not increased and incentives for industrial fishing are reduced. Unfortunately, small-scale fisheries usually receive little attention from policy makers, as is clearly seen by the lack of small-scale fishery catch data submitted by member countries to the FAO.

Stakeholders’ opinions and outlook

Stakeholders are essentially people with interests or concerns in a process and its outcomes. Generally, these can be employees, directors, owners/ shareholders, consumers, government, or the community from which the business draws its resources. When we refer to stakeholders in reference to blue growth, these extend to such a wide demographic that almost anyone could be considered a stakeholder – the entire population of the planet will be affected, in one way or another, by blue growth (or the lack thereof). However, we try to focus on stakeholders who have some direct influence as well as immediate interest, and hence who could potentially be part of a solution to achieving blue growth, and thereby contributing to sustainable development. Examples would be owners or managers of fishing companies, fishermen themselves, and government employees. Scientists are also an influential stakeholder group. These stakeholders have the power to make or influence important decisions, and thus are crucial for the actual implementation of blue growth and sustainable development. These are the people we must focus on when we communicate scientific findings that illuminate paths or policy changes that could lead to more sustainable outcomes.

In this issue we also include an article by Brian Clark Howard, who interviewed stakeholders; Jacqueline Alder from the FAO; Maria Damanaki from The Nature Conservancy; and Paul Holthus, the founding president of the World Ocean Council [6]. Gaining the perspective of these and other stakeholders is essential to the development of a common understanding of blue growth that policy-makers, scientists and business people alike can relate to and agree upon. Furthermore, successful blue growth itself is dependent on our ability to communicate across vastly different perspectives. It is not only scientists who hold the key to blue growth; without the cooperation of stakeholders there can be no blue growth no matter what the science and the data tell us. Cooperation and mutual understanding are not easily achieved, but they are essential to our success in achieving the goal of sustainable development.

The challenges

Although blue growth has a great deal of potential to secure sustainable use of the oceans, there are some clear challenges. One of the most apparent obstacles is the lack of a common and agreed -upon goal of blue growth. For some, blue growth revolves around maximizing economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources, but for others it means maximizing inclusive economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources and at the same time preventing degradation of blue natural capital. This lack of a common understanding may be the reason for the paucity of holistic blue growth strategies and more specific and inclusive goals and milestones that cut across sectors.

Another challenge is inter-disciplinarity – and learning how to “speak the same language”. Not only must scientists work together, across their diverse disciplines; but also scientists must work with policy experts and policy makers, together with other stakeholders who might have even more disparate interpretations of blue growth and other focal terms. Close collaboration with stakeholders is necessary to ensure that research informs and supports viable, integrated, and comprehensive solutions and their implementation. In theory, this seems doable, once the data are in and the conclusions are clear, and communicated to the politicians and policy makers.

Identification of knowledge gaps, which clearly depend on one's viewpoint, is another key challenge. What a scientist thinks is a critical knowledge gap may seem inconsequential to the government body deciding what to fund, and an obvious gap in knowledge for a politician that is critical to a policy decision might also be something that scientists are not focused on. Stakeholders in the industry might have a third idea of what are the critical gaps in knowledge that need to be assessed in order to create sustainable businesses. Again, communication is key here, although power imbalances caused by availability of funding must be closely monitored to avoid biased research, and biases in the knowledge that we gain from research.

Another challenge is how to resolve conflicts of interests, which are often rooted in tradeoffs between different uses of the ocean space, but also often concern who decides what should be open for public debate. For example, in Norway, salmon farming has emerged as an important industry in the national economy, and the sector has pioneered improvements in feeding practices, resource efficiency, and environmental performance per unit of production [14,15]. However fish farming can have significant environmental and biological impacts in the ocean, which affects other uses of the ocean space. Comprehensive

analysis of tradeoffs between different ocean uses requires coordination among and cooperation from very different scientific disciplines and stakeholders. Resolving conflicts between stakeholders is difficult and requires

holistic approach to governance.

Despite these challenges, blue growth has the potential to facilitate collaboration and communication among scientists, industry, and politicians and thereby lead to a coordinated effort to combat the effects of climate change and

anthropization. These challenges require additional research and would benefit from co-development with stakeholders. We hope the work laid out in this Special Issue lays the foundation for this to proceed in the future.

Toward a deeper understanding of blue growth

In this Special Issue, we have assembled a broad spectrum of papers that discuss blue growth from a diversity of

disciplines. Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research is of prominent importance when discussing the challenges and opportunities for blue growth, especially as one major challenge is to obtain efficient communication between the involved disciplines. Indeed, interdisciplinary dialogues, like this special-issue collection of papers provides,

necessitate that we understand each others’ terminology and concepts. The collection of papers in this Special Issue is meant as a contribution in this connection. In addition to the within-science dialogues, we also need to have a clear and comprehensible dialogue with stakeholders, as reflected in this collection.

ROVs

or UUVs - Are generally smaller unmanned underwater vessels,

than their crewed counterparts,

without life support, making them cheaper to build and

operate.

EUROPEAN

UNION COMMITTED TO RESEARCH AND INNOVATION THROUGH THE HORIZON EUROPE WIDENING PROGRAMME - 29 AUGUST 2022

Research and innovation capacity of Member States, Outermost Regions and Associated countries that underperform in terms of R&I performance is a key priority for Horizon Europe.

What is Horizon Europe Widening?

The ability to conduct successful transnational research and innovation projects in the EU varies from country to country. Some are more disadvantaged than others be it in the form of a lack of scientific infrastructure, ability to establish or access networks, maintain and retain talents or overcoming structural barriers at institutional, regional or national level.

Under Horizon Europe, the European Commission seeks to bridge these gaps by literally ‘Widening’ the scope of funding to strengthen research and innovation across Europe as a whole.

Participating countries and subsequent projects in the programme are able to upgrade their research and innovation systems, making them stronger and allowing the EU as a whole to advance together, in line with the policy objectives of the European Research

Area.

Developments in Cyprus are good example. In an effort to overcome some structural limits in the investment of Cyprus’s landscape in research, technology development and innovation (RTDI) it has been identified as one of the key beneficiaries of the Widening programme.

Under the Horizon Europe Widening programme a number of projects in different domains are implemented, in line with the smart specialisation strategies of the region to promote the country’s economic competitiveness and sustainability.

The Marine and Maritime Research, Innovation and Technology Centre of Excellence (CMMI) project is a concrete example. It seeks to play a key role in the country’s economic and social transformation by setting up the Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute (CMMI).

CMMI the Centre itself, has been established under the H2020 project CMMI-MaRITec and is aiming at driving sustainable Blue Growth by addressing the needs of industry and society within the spectrum of marine and maritime sectors.

Blue growth refers to the EU’s blue economy initiative, part of the European Green Deal. It seeks to mitigate the effects of climate change by developing offshore renewable energy, decarbonizing maritime transport and greening ports with a strong focus on Europe’s ‘Blue’ seas. This H2020 funding will propel the next generation of Cyprus based researchers and overall contribute towards greater research and innovation.

MORE EU INFORMATION:

All organisations eligible in Horizon Europe can participate in the Widening actions but only organisations based in Widening countries can participate as coordinators. Widening countries are less performing in terms of research and innovation with respect to the average EU 27. According to the

Horizon Europe regulation the Widening countries are: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and all associated countries with equivalent characteristics in terms of R&I performance and the Outermost Regions.

REFERENCES

[1] G. Brundtland, M. Khalid, "UN Brundtland Commission Report." Our Common Future, 1987.

[2] Boonstra, et al. This issue.

[3] Burgess, et al. This issue.

[4] COM, Innovation in the blue economy: Realizing the potential of our seas and oceans for jobs and growth.

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, in: Proceedings of the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Brussels, European Commission, 2014.

[5] Hilborn, Costello. This issue.

[6] B.C. Howard. This issue.

[7] Klinger, et al. This issue.

[8] A. Legat, V. French, N. McDonough - An economic perspective on oceans and human health

J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. (2015), pp. 1-5

[9] J. Lubchenco, E. Cerny-Chipman, J.N. Reimer, S.A. Levin - The right incentives enable ocean sustainability successes and provide hope for the future PNAS, 113 (51) (2016), pp. 14507-14514

[10] A. Najam, C. Cleveland - Energy and sustainable development at global environmental summits: an evolving agenda. Int. J. Environ. Sustain., 5 (2) (2003), pp. 117-138

[11] Niiranen, et al. This issue.

[12] Pauly. This issue.

[13] Soma, et al. This issue.

[14] - Geir Lasse Taranger, et al. - Risk assessment of the environmental impact of Norwegian Atlantic salmon farming ICES J. Mar. Sci., 72.3 (2014), pp. 997-1021

[15] - Trine Ytrestøyl, Turid Synnøve Aas, Torbjørn Åsgård Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway Aquaculture, 448 (2015), pp. 365-374

The above was information about the European Union's blue

growth assessments from 2014 to 2016 studies. There was no

clean up plan for ocean plastic waste, and single use

plastic continues to be used for packaging in supermarkets -

as if there were no problem. The Commission's maritime

policies were no better than the UN's at addressing the some

of the biggest issues of our time. We remain hopeful that as

the cost of food continues to rise, alongside the energy

crisis, that those responsible for policy are replaced by

more proactive personnel, along with the politicians who

failed to make a difference. This will only happen as the

public become more aware of the issues, and vote for

advocates who understand about food security, and health

issues arising from the consumption of contaminated,

toxin

laden, seafood.