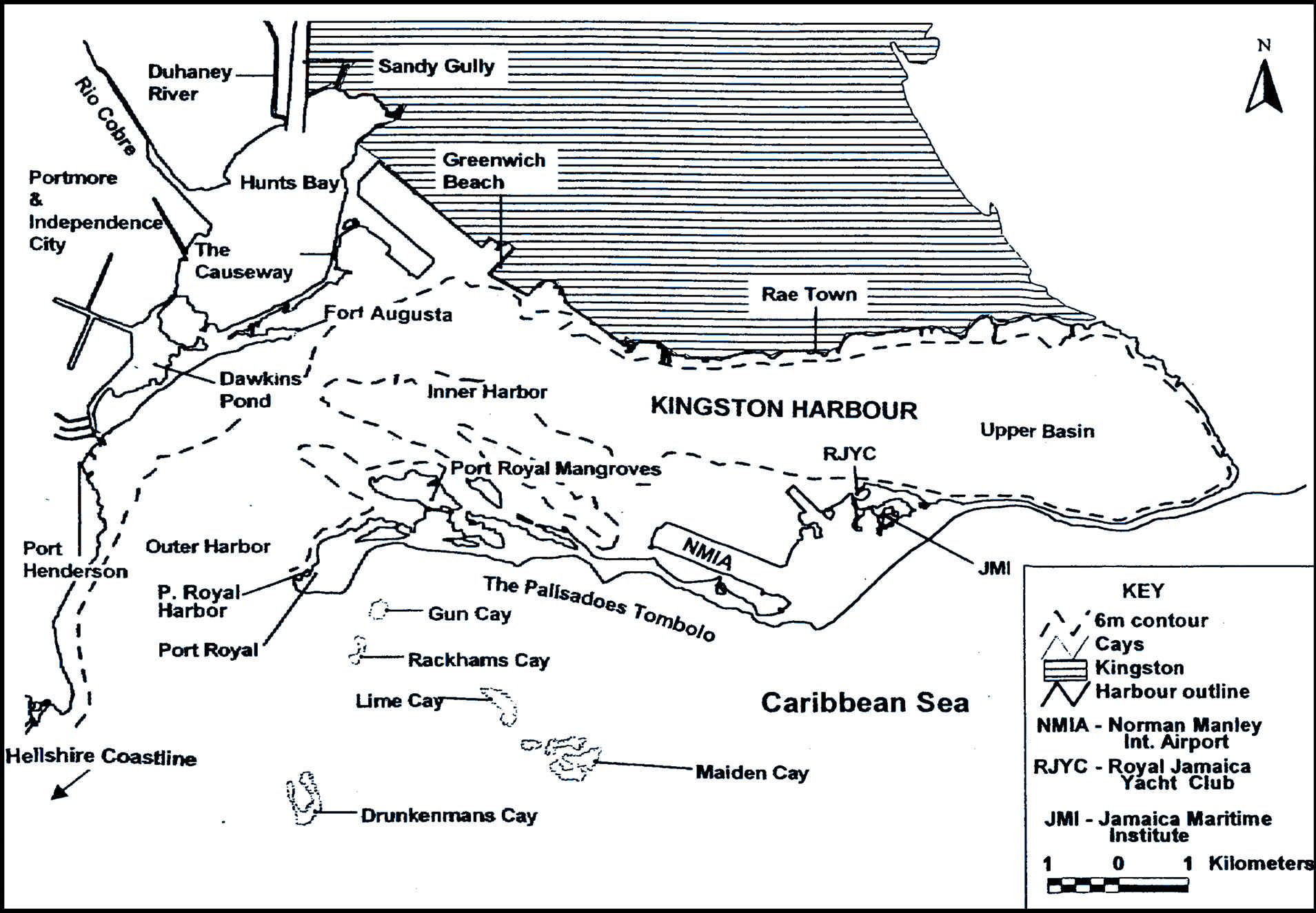

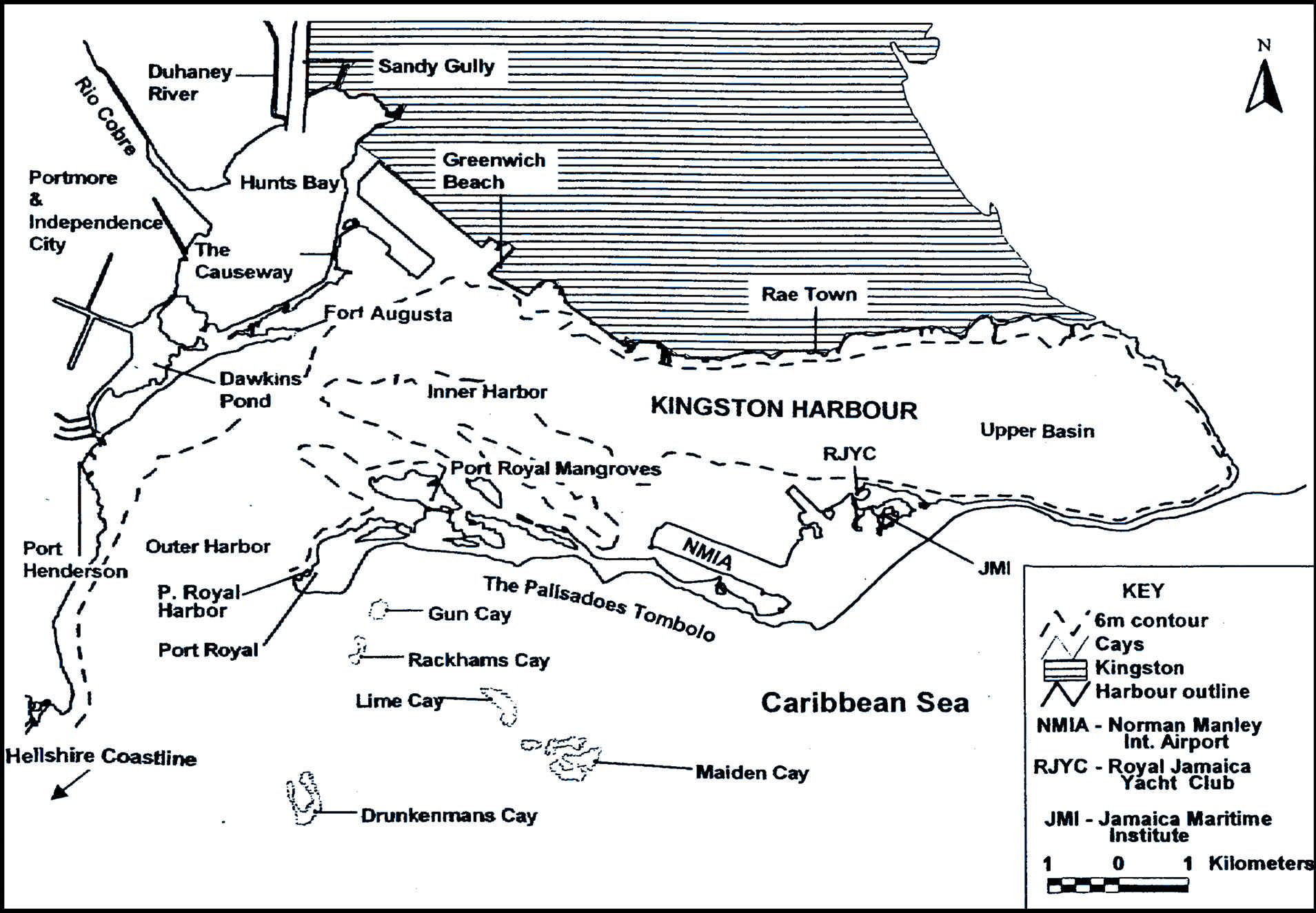

Palisadoes

Cemetery was home to the grave of the pirate captain Sir Henry

Morgan,

interned in a stone mausoleum, in a coffin made of iron

wood. Palisadoes, is a word of Portuguese origin. It is a thin tombolo of sand that

served as a natural protection for Kingston Harbour, Jamaica. Norman Manley International Airport and the historic town of Port Royal are both on Palisadoes.

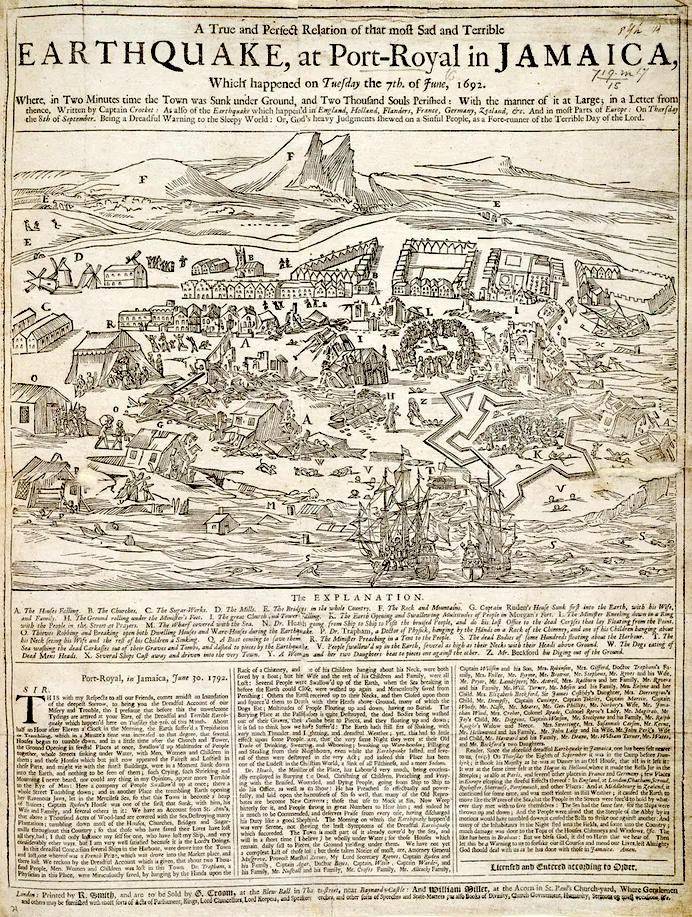

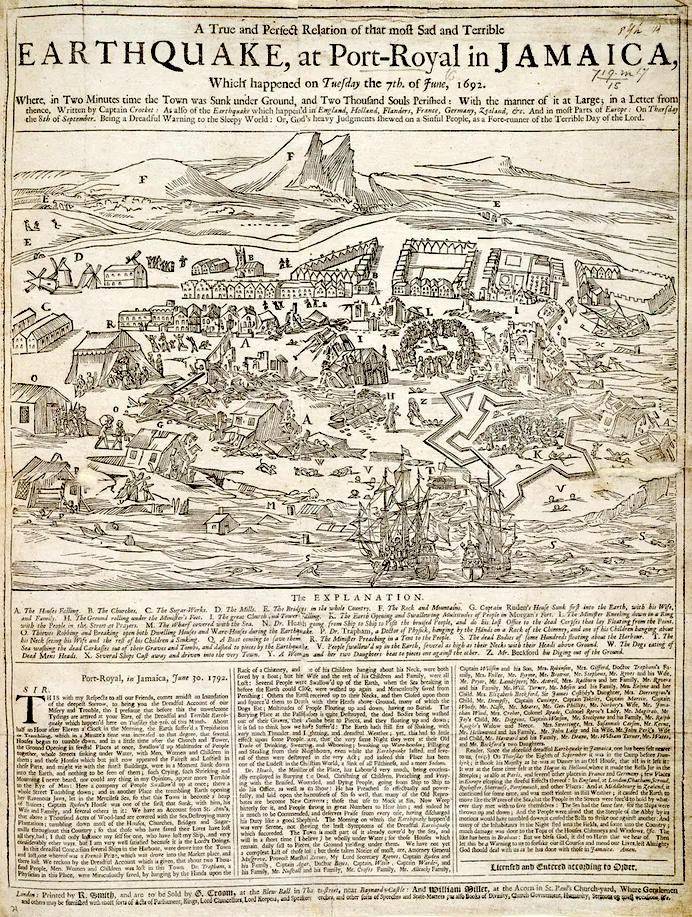

An

earthquake in the Caribbean

struck Port Royal, Jamaica, on

the 7th of June 1692. A stopped pocket watch found in the harbor during a 1959 excavation

conducted by Edwin

Link and his wife Marion, indicated that the resultant tsunami occurred around 11:43 AM local time.

TOMBOLO

A tombolo is a sandy or shingle isthmus. A tombolo, from the Italian tombolo, meaning 'pillow' or 'cushion', and sometimes translated incorrectly as ayre (an ayre is a shingle beach of any kind), is a deposition landform by which an island becomes attached to the mainland by a narrow piece of land such as a spit or bar. Once attached, the island is then known as a tied island.

Several islands tied together by bars which rise above the water level are called a tombolo cluster. Two or more tombolos may form an enclosure (called a lagoon) that can eventually fill with sediment.

NORMAN MANLEY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

Norman Manley International Airport (IATA: KIN, ICAO: MKJP), formerly Palisadoes Airport, is an international airport serving Kingston, Jamaica, and is located south of the island 19 km (12 mi) away from the centre of New Kingston. It is the second busiest airport in the country after Sangster International Airport, recording 629,400 arriving passengers in 2020 and 830,500 in 2021. Over 130 international flights a week depart from Norman Manley International Airport. Named in honour of Jamaican statesman Norman Manley, it is a hub for Caribbean Airlines. It is located on the Palisadoes tombolo in outer Kingston Harbour; it fronts the city on one side and the

Caribbean Sea on the other.

A

diver using SCUBA gear to explore Port Royal

DAMAGE

Two-thirds of the town, about 13 ha (33 acres), sank into the sea immediately after the main shock. According to Robert Renny in his An History of Jamaica (1807): "All the wharves sunk at once, and in the space of two minutes, nine-tenths of the city were covered with water, which was raised to such a height, that it entered the uppermost rooms of the few houses which were left standing. The tops of the highest houses were visible in the water and surrounded by the masts of vessels, which had been sunk along with them."

Before the earthquake the town consisted of 6,500 inhabitants living in about 2,000 buildings, many constructed of brick and with more than one storey, and all built on loose sand. During the shaking, the sand liquefied and the buildings, along with their occupants, appeared to flow into the sea. More than twenty ships moored in the harbour were capsized. One ship, the frigate Swann, was carried over the rooftops by the tsunami. During the main shock, the sand was said to have formed waves. Fissures repeatedly opened and closed, crushing many people. After the shaking stopped the sand again solidified, trapping many victims. Palisadoes cemetery, where the grave of the former pirate Sir Henry Morgan was located, was one of the parts of the city to fall into the sea; his body has never been found.

At Liguanea (present-day Kingston), all the houses were destroyed and water was ejected from 12 m (40 foot) deep wells. Almost all the houses at St. Jago (Spanish Town) were destroyed.

Many landslides occurred across the island. The largest, the Judgement Cliff landslide, displaced the land surface by up to 800 m and killed 19 people. Several rivers were temporarily dammed and a few days after the earthquakes the harbour became flooded with large numbers of trees stripped of their bark brought down after one of these dams was breached.

A pocket watch, made in the Netherlands by the French maker Blondel in about 1686, was recovered during underwater archaeological investigations led by Edwin Link in 1959. The watch was stopped with its hands pointing to 11:43 AM; this matches well with contemporary accounts of the timing of the earthquake.

Visibility

is typically very poor. On this dive, the water was relatively clear,

good news for the team surveying the site.

AFTERMATH

Even before the destruction was complete, some of the survivors began looting, breaking into homes and warehouses. The dead were also robbed and stripped, and, in some cases, had fingers cut off to remove the rings that they wore.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, it was common to ascribe the destruction to divine retribution on the people of Port Royal for their sinful ways. Members of the Jamaica Council declared: "We are become by this an instance of God Almighty's severe judgement." This view of the disaster was not confined to Jamaica; in Boston, the Reverend Cotton Mather said in a letter to his uncle: "Behold, an accident speaking to all our English America".

After the earthquake, the town was partially rebuilt. But the colonial government was relocated to Spanish Town, which had been the capital under Spanish rule. Port Royal was devastated by a fire in 1703 and a hurricane in 1722. Most of the sea trade moved to Kingston. By the late 18th century,

Port Royal was largely abandoned.

HOW

THE EARTHQUAKE AFFECTED FORWARD ARCHITECTURE & BUILDING DESIGN

The shock created by the 1692 earthquake jolted the heavy brick and stone structures in Port Royal to their foundations because the rigid building materials did not allow for any shock resistance.

That is why in Japan, traditional houses features paper walls and timber

construction.

Scientists propose that at the time of the earthquake, a process known as “liquefaction”

occurred beneath Port Royal. Liquefaction occurred when the water rushed underneath

the foundation of the town turning the individual particles of sand into a liquefied state resembling quicksand. In turn, the watery sand could not support the tall, heavy

buildings and the most affected structures sank into the harbor. The process of

liquefaction is evident by the results of earthquake damage which caused Forts James and

Carlisle along with Thames, Queen, and High streets to slide into the

sea. These results indicate that the earthquake did not simply shake the brick and stone structures so as to shift their foundations and eventually topple to the ground, but rather moved the sandy foundations downward, so that many of the buildings situated on the streets closest to the ocean were submerged intact with their upper stories remaining above water.

After the destruction of Port Royal, the English were faced with the dilemma of

what types of structures to build in place of the ones that failed to survive the shocks of the earthquake. Colonists had the choice to re-build in the popular English style

characterized by multi-story buildings constructed with heavy building materials or to re-evaluate their previous methods to better suit their new environmental circumstances. An eyewitness to the disaster noted that the low lying buildings constructed of

timber were among some of the only structures surviving after the earthquake.

Homes

that float and are (simply) flexibly tethered, constructed of wood,

are now installed in some flood prone areas. Thus in the case of Acts

of God, or Divine Intervention, they would not sink, or crumble, but

float and move.

Quaker John Pike similarly observed that the earthquake “hath not left a house standing in the whole place that was built of either stone or brick, nor anything that was built with the same materials” and that colonists “now think a Negro‟s house that is daubed with mortar and thatched... a pleasant house.”

Although Kingston existed across the harbor, Port Royal was rebuilt after the

earthquake with wooden buildings which could withstand an earthquake, but these

structures were defenseless against fire. In those times they did not

have fire retardant treatments for timber.

On January 9, 1703, fire destroyed all the

structures in Port Royal except for one building and two fortifications. Port Royal was

rebuilt again after the fire, and according to contemporary Francis Rogers, many of the

houses were rebuilt with brick but none were more than two stories high and were fitted

with large windows for “coolness.”

This observation reveals that colonists adapted

their structures to the various natural calamities in which they faced. The second

rebuilding of Port Royal exemplifies the tension labeled by Jack Greene as “inheritance”

versus “experience.” In summation, after the earthquake, colonists realized that the

multi-storied brick buildings were not practical and rebuilt with mostly wooden

structures; however, after the 1703 fire destroyed Port Royal again, colonists reverted

back to their brick structures with modifications to windows and restrictions on building height.

Colonists inherited their construction methods and their desire to use materials such as brick because this embodied the English culture. Colonists‟ reversion to less

flammable brick after the fire illustrates further adaptation of their building styles to better suit their foreign environment.

During the process of learning to survive in the tropics, the English colonists

gradually employed many of the time-tested Spanish building techniques, after observing

their ability to withstand Jamaica‟s natural environment first-hand.

Where at first they scorned such designs.

CHARACTERISTICS

Earthquake

There were three separate shocks, each with increasing intensity, culminating in the mainshock. The estimated size of the event was 7.5 on the moment magnitude scale.

Despite reports of the town flowing into the sea, the main result of the earthquake was subsidence caused by liquefaction. This would also explain an eyewitness account of houses being swallowed and people being buried up to their necks in the sand. The probable triggering of the Judgement Cliff landslide during the earthquake occurred along the line of the Plantain Garden fault. Movement on this structure has been suggested as the cause of the earthquake.

Landslides

The Judgement Cliff landslide is a complex rock-slide slump with a volume of about 131–181 × 106 m3. The slip surface is found within zones of clay and shale with gypsum at the base of a limestone unit. This landslide occurred after the earthquake but it remains possible that heavy rain over the few days after the event, or possibly during a hurricane in October later that year was the final trigger for the slip.

Tsunami

The sea was observed to retreat by about 300 yd (270 m) at Liguanea (probably near Kingston) while at Yallahs it withdrew 1 mi (1.6 km). It returned as a 6 ft (1.8 m) high wave that swept over the land. One possible cause of the tsunami is thought to be the slump and grain flow into the harbour from beneath the town itself, although the waves in the harbour may be better described as seiches and larger waves reported elsewhere, such as at Saint Ann's Bay, are explained as the result of an entirely separate submarine landslide, also triggered by the earthquake.

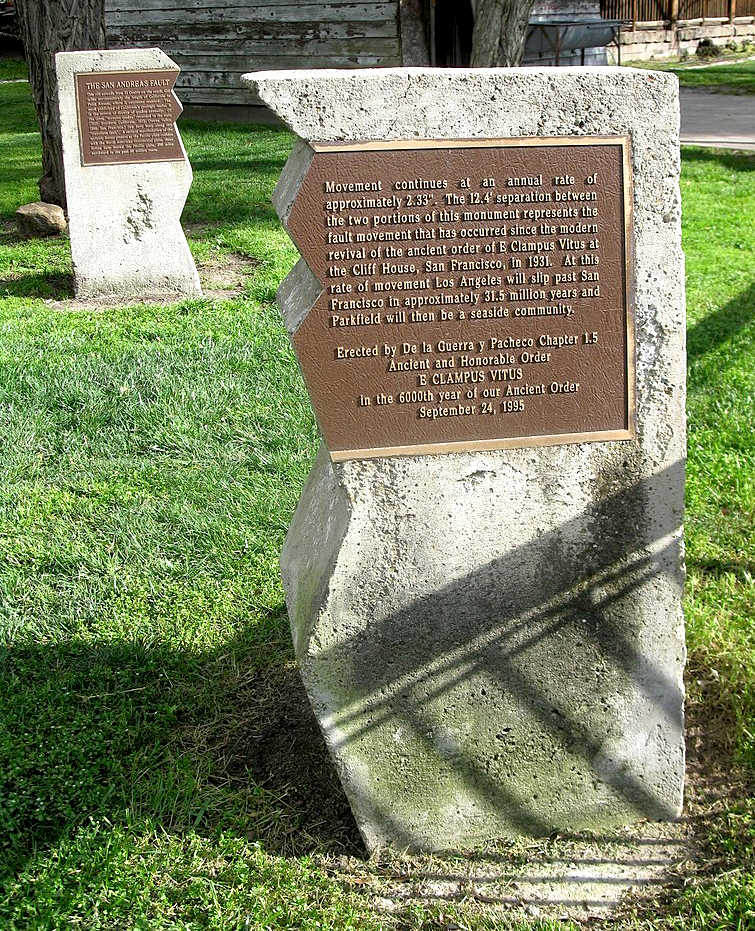

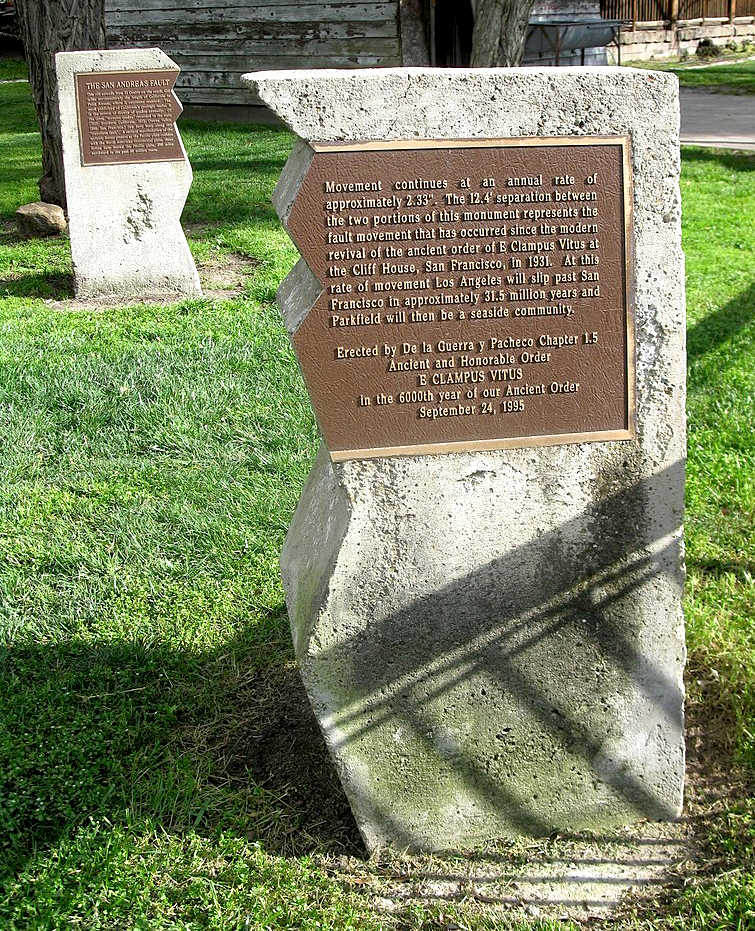

Examples

of aseismic creep. The house on the left was demolished. The stone

markers are a simulation to illustrate movement, where it is so gradual,

it is hardly noticeable.

EYE

WITNESS ACCOUNT

Dr. Emmanuel Heath

was a rector for the Anglican Church ministering at Port Royal, Jamaica,

on the fateful day when earthquakes and a subsequent tsunami, subsumed

the city in around twenty or so minutes.

He

described the dreadful

Earthquake, that

happened at Port Royal in Jamaica, on June the 7th, 1692; in two lengthy

letters to a friend. In 2022, the underwater

city is on a tentative list for inclusion as a UNESCO

World Heritage Site.

Captain

Sir Henry Morgan was a pirate, and privateer, ending up as the Governor of

Jamaica. He was buried at Palisadoes

Cemetery, then Port Royal was washed

into the Caribbean Sea, the result of an earthquake and

tsunami in 1692. Not to be

seen again for 300 years.

UNDERWATER

ARCHAEOLOGY EXCAVATION IN PORT ROYAL

Underwater explorations and excavations have been conducted in Port Royal over the years. Here is a listing of such excavations. After the 1692 earthquake, people tried to salvage anything considered to be valuable from the area, which became known as the Sunken City.

1859: Jeremiah Murphy a naval diver, using a diving bell located the remains of Fort James.

1956 - 1959: Edwin Link dug test pits in the King's Warehouse and Fort James.

1960:

Norman Scott explored Fort Carlisle.

1965 - 1968: Robert Marx excavated between twenty to thirty buildings in the Sunken City.

1969

- 1970: Philip Mayes Excavation. Mayes was hired by the Jamaican National Trust Commission to continue research. Mayes is accredited with uncovering

St. Paul’s Church of Port Royal, the largest building of the 17th century city.

1981 - 1990: Institute of Nautical Archaeology of the Texas A&M

(Agricultural & Mechanical) University in close cooperation with the Archaeology Division excavated buildings near the intersection of Queen and High Street.

Port Royal mangroves: Hurricane Refuge lagoon, Fort Rocky lagoon and Cemetery lagoon